Getting an insurance claim denied is frustrating wherever you live. You’ve paid your premiums, something’s gone wrong, and now the insurer says they won’t pay out. What happens next, though, depends enormously on which side of the Atlantic you’re standing.

British policyholders have access to a free dispute resolution service that can order insurers to pay up to £430,000. American policyholders facing the same situation often find themselves choosing between accepting an unfair denial or hiring lawyers and going to court. The systems aren’t just different in degree—they’re built on entirely different philosophies about how disputes between consumers and financial institutions ought to be resolved.

This comparison sets out what each country actually offers when your insurer says no, and why UK consumers have protections that Americans can only envy.

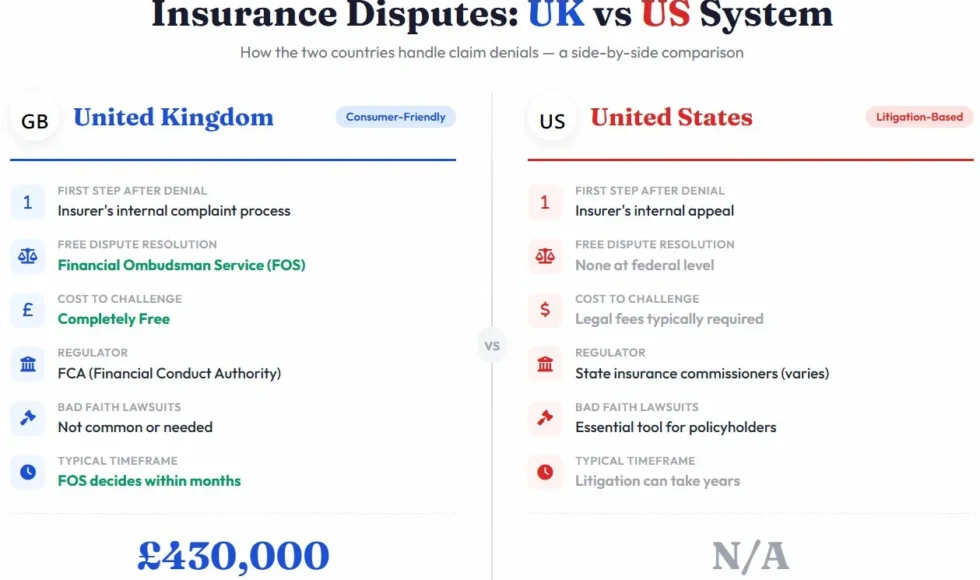

The Basic Difference: A Side-by-Side View

Before getting into specifics, here’s how these two systems compare across the key factors that matter when you’re facing a claim denial.

| Aspect | UK System | US System |

|---|---|---|

| First step after denial | Insurer’s internal complaint process | Insurer’s internal appeal |

| Free dispute resolution | Financial Ombudsman Service | None at federal level |

| Cost to challenge denial | Free (FOS) | Legal fees typically required |

| Regulator | FCA (Financial Conduct Authority) | State insurance commissioners (varies by state) |

| Bad faith lawsuits | Not common or needed | Essential tool for policyholders |

| Typical timeframe | FOS decides within months | Litigation can take years |

| Maximum award (free route) | £430,000 | N/A—no equivalent exists |

The contrast is rather stark. The UK built a system specifically designed so ordinary people can challenge insurers without needing lawyers or spending money. The US left policyholders to sort it out themselves, with litigation as the primary recourse when negotiation fails.

The UK’s First Line of Defence: Financial Ombudsman Service

The Financial Ombudsman Service exists precisely for situations where you’ve complained to your insurer and gotten nowhere. It’s free, it’s independent, and its decisions are binding on insurers if you accept them.

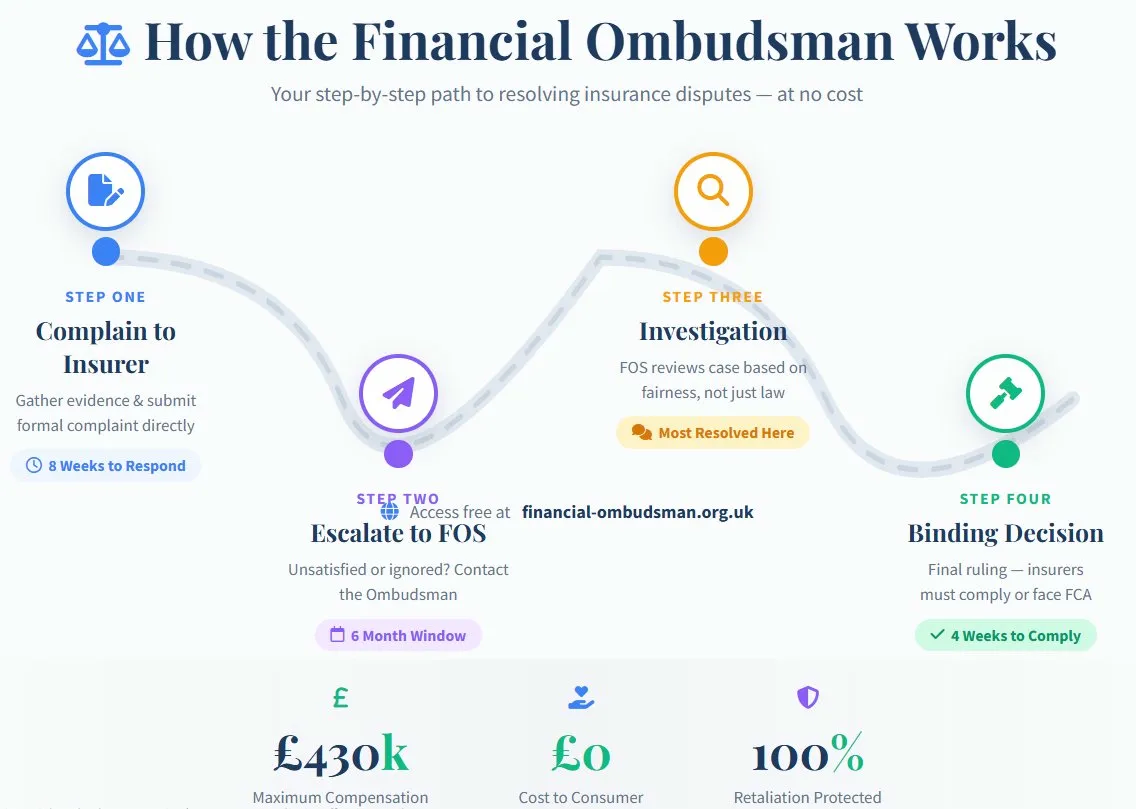

How FOS Actually Works

The process has a logical sequence that doesn’t require legal training to navigate.

- Step one is complaining to your insurer directly. You gather your evidence—policy documents, correspondence, photos, whatever supports your position—and submit a formal complaint. The insurer then has 8 weeks to issue what’s called a final response letter. If they don’t respond within that window, you can escalate anyway.

- Step two is contacting FOS if you’re unsatisfied with the insurer’s response or they’ve ignored you. You’ve got 6 months from the final response letter to do this, or you can escalate after 8 weeks of silence. The service is accessed through financial-ombudsman.org.uk—no forms to pay for, no lawyers to hire.

- Step three is investigation. FOS checks whether your complaint falls within their remit, requests information from the insurer, and assigns an investigator to review everything. Most disputes get resolved at this stage through phone calls or written communication. The investigator looks at what’s fair, not just what’s technically legal.

- Step four involves formal decisions if the investigation doesn’t resolve things. An initial view gets issued, and either party can request escalation to an ombudsman for a final binding decision. If you accept that decision, the insurer must comply—there’s no wriggling out of it.

The Numbers That Matter

FOS can order insurers to pay compensation up to £430,000 for complaints made from April 2024 onwards. That limit increased from £375,000, reflecting that insurance disputes can involve substantial sums.

Insurers who receive an adverse FOS decision must comply within 4 weeks. If they don’t, the matter escalates to the FCA, which has powers to fine firms and take regulatory action. Non-compliance isn’t really an option for insurers who want to keep operating.

The whole process costs consumers nothing. FOS is funded by levies on financial services firms, not by charging the people who use it. You can’t be charged for making a complaint, and insurers are prohibited from retaliating against customers who escalate to the ombudsman.

The US System: No Ombudsman, More Lawyers

Americans facing insurance claim denials operate in a fundamentally different environment. There’s no equivalent to FOS at the federal level, and state-level options are limited in what they can actually accomplish for individual policyholders.

What State Insurance Commissioners Actually Do

Each US state has an insurance commissioner or department that regulates insurers operating within that state. These bodies handle licensing, monitor insurer solvency, and can take action against companies engaging in patterns of misconduct.

What they generally don’t do is resolve individual claim disputes. You can file a complaint, and the department might contact the insurer on your behalf, but they lack the authority to order an insurer to pay a disputed claim. They’re regulators, not adjudicators.

Some states have more consumer-friendly processes than others, but the variation is substantial. A policyholder in California faces different options than one in Texas or Florida. There’s no unified federal standard for how claim disputes get handled.

When Negotiation Fails

American policyholders who can’t resolve disputes directly with their insurer face a choice that UK consumers largely avoid: accept the denial or hire a lawyer and potentially go to court.

This is where the systems diverge most sharply. In the US, policyholders confronting stonewalling from insurers frequently discover that engaging a denied insurance claim lawyer becomes the only realistic path to getting insurers to respond seriously. Unlike UK consumers who escalate to FOS without spending a penny, Americans must often invest in legal representation just to level the playing field.

The economics of this are brutal for smaller claims. If your insurer has denied a £5,000 claim, hiring lawyers to fight it might cost more than the claim is worth. UK policyholders take the same dispute to FOS for free. American policyholders either accept the loss or spend money they might not recover.

Why Lawyers Become Necessary

It’s not that American policyholders are more litigious by nature. The system essentially requires legal involvement for disputed claims of any significant value because no free alternative exists.

Insurance companies employ teams of lawyers and adjusters whose job is to minimise payouts. An individual policyholder negotiating alone is at a substantial disadvantage—they don’t know the technical rules, don’t understand what constitutes bad faith, and can’t credibly threaten consequences that insurers care about.

Lawyers change that dynamic. They know how to document bad faith conduct, understand what discovery might reveal, and can file lawsuits that create actual risk for insurers. The threat of litigation, and the costs and exposure it brings, often motivates settlements that wouldn’t happen otherwise.

UK Regulatory Framework: FCA Rules on Claim Handling

Beyond FOS, the UK has a regulatory structure that sets baseline standards for how insurers must handle claims. This comes from the Financial Conduct Authority through the Insurance Conduct of Business Sourcebook, specifically ICOBS Chapter 8.

What ICOBS 8.1 Requires

The core principles are straightforward. Insurers must handle claims promptly and fairly. They must provide reasonable guidance to help policyholders make claims and keep them updated on progress. They cannot unreasonably reject claims, including through policy termination or avoidance. Once settlement terms are agreed, they must pay promptly.

Unreasonable Rejection Standards

ICOBS 8.1.2R and 8.1.3R set out when rejections are considered unreasonable. Insurers can’t reject claims based on non-qualifying misrepresentations—minor errors that didn’t actually affect the risk. They can’t rely on warranty breaches or term violations unless those breaches connect to the actual claim and comply with the Insurance Act 2015.

Fraud is obviously different—insurers can reject fraudulent claims. But the bar for proving fraud is high, and insurers can’t simply allege it to avoid paying legitimate claims.

Outsourcing Doesn’t Excuse Bad Conduct

Some insurers use third-party claims handlers. ICOBS makes clear that responsibility remains with the insurer regardless. If the outsourced handler treats policyholders unfairly, the insurer bears regulatory responsibility.

FCA Enforcement Powers

The FCA can fine insurers for systematic failures in claim handling. These aren’t small fines—major insurers have faced penalties in the millions for conduct issues. The threat of regulatory action creates incentives for fair treatment that exist independently of individual complaints.

US Regulatory Comparison

The US lacks any equivalent unified federal standard. State regulations vary significantly, and enforcement depends on individual state insurance departments’ resources and priorities. Some states have robust consumer protection frameworks; others are notably more insurer-friendly.

This patchwork approach means American policyholders’ protections depend heavily on where they live and which state’s law governs their policy.

Insurance Act 2015: Proportionate Remedies

The Insurance Act 2015, which took effect in August 2016, fundamentally changed how non-disclosure and misrepresentation issues get handled in UK insurance contracts. The reforms protect policyholders from outcomes that would have been devastating under the old law.

The Old Problem

Before the Act, insurance contracts operated under a strict duty of utmost good faith. If a policyholder failed to disclose something material—even innocently, even something they didn’t realise mattered—the insurer could void the entire policy from inception. Premiums paid over years could be lost, and claims could be denied entirely, all because of innocent mistakes.

This was harsh. Policyholders who made genuine errors, or who didn’t understand what they were supposed to disclose, faced complete loss of coverage.

The New Approach: Duty of Fair Presentation

The Act replaced the old duty with a “duty of fair presentation of the risk.” Policyholders must disclose material circumstances they know or ought to know, present information in a reasonably clear and accessible way, and ensure representations are substantially correct.

But crucially, the remedies for breach are now proportionate to the insurer’s actual loss.

| Breach Type | Insurer’s Remedy |

|---|---|

| Deliberate or reckless | Avoid policy, retain premium, deny claims |

| Innocent, but insurer wouldn’t have insured at all | Avoid policy, return premium |

| Innocent, but insurer would have used different terms | Proportionate adjustment; claims paid as if on adjusted terms |

| Innocent, and wouldn’t have changed anything | No remedy for insurer |

This means an innocent mistake that would have resulted in a slightly higher premium doesn’t void your entire policy anymore. The insurer adjusts the claim proportionately, and you still get paid something.

Why This Matters for Claim Disputes

Under the old regime, insurers could and did use technical non-disclosure arguments to avoid paying legitimate claims. The policyholder forgot to mention something from years ago, and suddenly the whole policy was void.

The 2015 Act makes that much harder. Insurers must prove the breach actually would have affected their underwriting decision, and the remedy must match the actual impact. It’s a fundamental shift toward treating policyholders fairly rather than catching them out on technicalities.

US Bad Faith Laws: The Tool UK Doesn’t Really Need

American insurance law has developed a concept called “bad faith” that allows policyholders to sue insurers for unreasonable conduct in handling claims. This exists specifically because the US system lacks the consumer protections that make such lawsuits unnecessary in the UK.

What Bad Faith Means

Bad faith claims allege that an insurer acted unreasonably in denying, delaying, or underpaying a legitimate claim. Unlike a simple breach of contract claim—where you’re just seeking the policy benefits—bad faith claims can recover damages beyond the policy amount, including consequential damages and, in some states, punitive damages.

The specific rules vary by state. California, Texas, and Florida all have bad faith statutes, but they work differently. Some states are more plaintiff-friendly than others. Some require showing the insurer knew the claim was valid; others use a reasonableness standard.

Why Bad Faith Litigation Exists

Bad faith lawsuits are essentially a market solution to a regulatory gap. Because the US doesn’t have FOS-style dispute resolution or unified FCA-style conduct rules, the courts became the venue for policing insurer behaviour.

The threat of bad faith liability creates some deterrent against the worst conduct. Insurers who routinely deny valid claims, delay payments unreasonably, or engage in lowball tactics face potential lawsuits that can cost far more than simply paying claims properly.

But it’s an expensive, time-consuming deterrent that works better for large claims than small ones and better for policyholders who can afford lawyers than those who can’t.

Why UK Doesn’t Rely on This

British policyholders don’t need bad faith lawsuits because the system provides other routes. FOS handles individual disputes for free. The FCA enforces conduct standards and can fine insurers for systematic failures. The Insurance Act 2015 prevents technical avoidance of legitimate claims.

Bad faith litigation exists in the US because the system lacks these alternatives. It’s not that Americans prefer lawsuits—it’s that lawsuits are often the only tool available.

Time and Cost: What Each System Demands

The practical burden of challenging an insurance denial differs dramatically between these two countries.

The UK Route

Internal complaint: Submit to insurer, wait up to 8 weeks for response.

FOS escalation: If unsatisfied, file with FOS within 6 months of final response.

FOS resolution: Typically 3-6 months, sometimes longer for complex cases.

Total cost to policyholder: Nothing. Zero. The service is free.

The system is explicitly designed for accessibility. Ordinary people with no legal training can navigate it. No lawyers required unless you choose to involve them.

The US Route

Internal appeal: Submit to insurer, wait weeks to months depending on state requirements and insurer practices.

Regulatory complaint: File with state insurance commissioner, but don’t expect them to adjudicate your specific dispute.

Negotiation: Attempt to resolve directly, potentially with legal help.

Litigation: If negotiation fails, file lawsuit. Expect 1-3 years for resolution, possibly longer.

Total cost to policyholder: Legal fees, court costs, potentially expert witnesses. Even contingency-fee arrangements take a substantial percentage of any recovery.

The American system works reasonably well for large claims where the economics justify legal involvement. For smaller claims—the kind ordinary consumers actually face—it often doesn’t work at all.

When UK Policyholders Still Need Lawyers

FOS handles most consumer insurance disputes effectively, but it’s not the right solution for every situation.

Commercial Policies

FOS primarily serves consumers and small businesses. Large commercial insurance disputes involving complex policies and substantial sums may fall outside their jurisdiction or exceed their practical capacity to resolve.

Claims Exceeding £430,000

The compensation limit means very high-value claims might require court proceedings to recover fully. Property claims, professional indemnity matters, and certain liability situations can exceed this threshold.

Precedent-Setting Issues

FOS decides what’s fair in individual cases, but doesn’t create binding legal precedent. If your dispute raises a novel legal question that needs authoritative resolution, court proceedings might be necessary.

Disputes With Overseas Insurers

FOS jurisdiction primarily covers firms authorised in the UK. Disputes with insurers based elsewhere may require different approaches.

But for the vast majority of consumer insurance disputes—home insurance, motor insurance, travel insurance, life insurance claims—FOS provides effective resolution without legal costs. The exceptions exist, but they’re exceptions.

What This Comparison Shows

The UK and US have made fundamentally different choices about how to handle disputes between insurance companies and the people they’re supposed to protect.

Britain built an accessible, free system specifically designed so consumers don’t need lawyers to challenge unfair denials. FOS, FCA regulation, and the Insurance Act 2015 work together to create multiple layers of protection that function without requiring policyholders to fund litigation.

America left the matter largely to the market and the courts. State regulators oversee insurers but generally don’t resolve individual disputes. Bad faith laws provide some recourse, but accessing that recourse requires legal investment that many policyholders can’t afford or can’t justify for smaller claims.

British consumers sometimes complain that FOS takes too long or that compensation limits should be higher. Fair points, both. But the fundamental architecture—free dispute resolution, binding decisions, regulatory enforcement—means UK policyholders have realistic options when insurers behave badly.

American consumers facing the same situations often discover their options are limited to accepting unfair treatment or spending money on lawyers with no guarantee of success. The system works for those with resources to fight. For everyone else, it’s rather less effective.

References

- Financial Ombudsman Service: https://www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk

- FCA Handbook ICOBS Chapter 8: https://www.handbook.fca.org.uk/handbook/ICOBS/8/

- Insurance Act 2015: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/4/contents

- Consumer Insurance (Disclosure and Representations) Act 2012: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/6/contents

- FOS Compensation Limits (2024): https://www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk/consumers/expect/compensation

- FCA Enforcement Powers: https://www.fca.org.uk/about/enforcement