Whether one is on the offence or the defence side, being charged with a sexual offence is a serious matter that can have devastating consequences. However, the legal frameworks in the United Kingdom (more specifically, England and Wales) and Queensland, Australia, have their own unique ins and outs that matter greatly to each individual navigating the system. This is not an overview — rather, this is an analysis of particular jurisdictions and how they each deal with the core legal components surrounding such allegations.

Legal Frameworks

UK (England and Wales): The Sexual Offences Act 2003 is the main legislative framework operating in the United Kingdom (England and Wales). It replaced the previous Sexual Offences Act 1956, and in doing that, it updated the provisions surrounding definitions, penalties, and even consent. This Act came into force on 1 May 2004.

Queensland: The Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) and the corresponding sections 347-352 that deal with rape and sexual assault. In September 2024, Queensland also made some significant amendments to the Criminal Code (Consent and Mistake of Fact) and Other Legislation Amendment Act, which made some adjustments to the provisions of consent.

| Aspect | UK (Sexual Offences Act 2003) | Queensland (Criminal Code 1899) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary legislation | Sexual Offences Act 2003 | Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) |

| Key sections for rape | Section 1 | Section 349 |

| Key sections for sexual assault | Section 3 | Section 352 |

| Last major reform | Ongoing amendments, 2022 Police Crime Sentencing and Courts Act | September 2024 consent reforms |

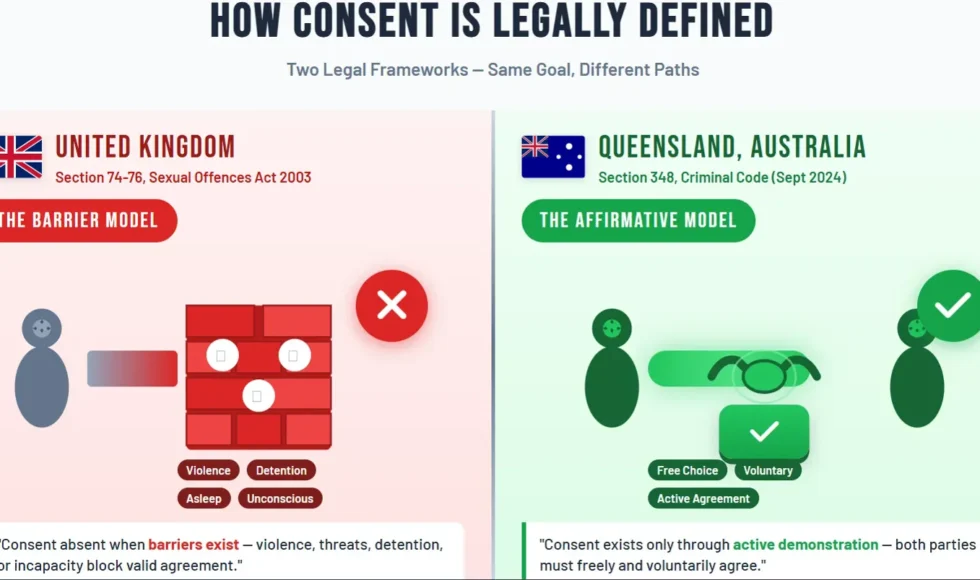

How Consent Is Defined

While the wording may be different, this is the area where the two systems have come to the same point.

In the UK, a Definition (Section 74, SOA 2003) states: A person consents if they “agree by choice, and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice.” There are presumption laws (Section 75) and lack of consent laws (Section 76) that deal with absent consent.

Section 75 is where evidence is presumptively given. This applies to the victim. They are claimed to have been detained, sleep, unresponsive, uncommunicative, or are in a physical state of incapacity. If the circumstance is present and the defendant is aware of it, the evidentiary burden of proving that the victim consented shifts to the defendant.

In Queensland, people are defined under law section 348 of the Criminal Code: as having the right to give consent if: it is given freely and voluntarily and the person has the mental capacity to give the consent. Since Sept 2024, Queensland has introduced a new model of affirmative consent.

Section 348(2) has examples of situations in which people state that they have given consent freely: the presence of force, threats, the presence of intimidation, the fear of physical damage, the use of power, tricks and fraud, and in situations where the victim is asleep, in a state of unconsciousness, or has been subjected to intoxication (i.e. use of alcohol or drugs) to the point that consent is impossible.

| Consent Element | UK | Queensland |

|---|---|---|

| Core definition | Agreement by choice with freedom and capacity | Free and voluntary agreement with cognitive capacity |

| Silence = consent? | No | No (explicitly stated since 2024) |

| Withdrawal of consent | Yes, consent can be withdrawn at any time | Yes, explicitly codified |

| Intoxication | May negate capacity to consent | May negate capacity to consent |

| Affirmative consent model | No (not required to take positive steps) | Yes (since September 2024) |

This article provides general information only and does not constitute legal advice. Anyone facing accusations should seek immediate representation from a qualified criminal lawyer in the relevant jurisdiction.

The Right to Silence: A Fundamental Difference

This is where the UK and the Australian systems start to differ the most, and is a difference that is important.

UK Position: The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 is the Act that most changed the UK position. Under Section 34 – 37, a court is able to make an “adverse inference” from one’s silence, in some situations. If questioned by police and you remain silent, but at trial present some facts in your defense that you could have reasonably stated during police questioning, the court will consider your silence to be evidence against you.

This is reflected in the police caution in England and Wales: “You have the right to remain silent. You may, however, be at a legal disadvantage if you do not say something during questioning about something you will rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence.”

You cannot be convicted based on an adverse inference. There must be a prima facie case, but the inference can support the prosecution’s case.Queensland Position: Queensland still has the old common law right to silence. There are no adverse inference provisions. Section 397 of the Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 still enshrines the right to remain silent.

In the case of Petty & Maiden v The Queen (1991), the High Court established that juries should be instructed that no adverse inference should be drawn against an accused for not providing any explanation to the police. The judge has to tell the jury not to consider the defendant’s silence.

| Right to Silence | UK | Queensland |

|---|---|---|

| Can silence be used against you? | Yes, in specific circumstances | No |

| Police caution | Warns that silence may harm defence | States right to silence without penalty |

| Adverse inference at trial | Permitted under CJPOA 1994 | Not permitted (Petty & Maiden) |

| Jury direction | May be told to consider silence | Must be told NOT to consider silence |

This difference is significant. In the UK, you need to seriously consider providing your account early — if you have a defence, there can be consequences for staying silent and raising it later. In Queensland, you can remain completely silent throughout and the jury cannot hold that against you.

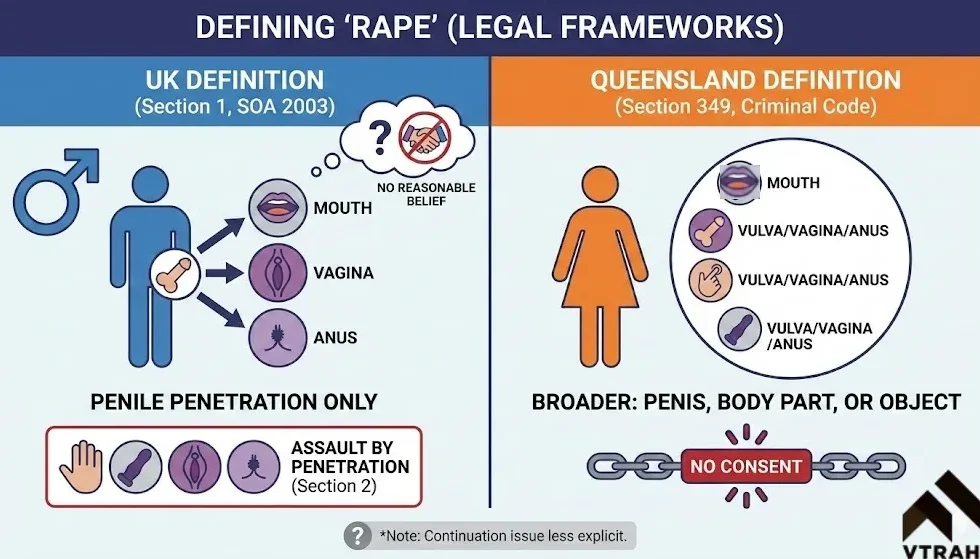

Definition of Rape

UK (Section 1, SOA 2003): Rape requires penile penetration of the vagina, anus, or mouth of another person without consent, where the defendant does not reasonably believe there is consent. Because rape requires a penis, the offence can only be committed by someone with a penis. Other forms of non-consensual penetration fall under “assault by penetration” (Section 2).

Queensland (Section 349, Criminal Code): Rape includes penile intercourse without consent, penetration of the vulva, vagina, or anus with any body part or object without consent, and penetration of the mouth with a penis without consent. The definition is broader than the UK’s “rape” category but Queensland’s statute doesn’t encompass the continuation of intercourse after consent is withdrawn in the same explicit way.

Maximum Penalties

Both jurisdictions treat sexual offences seriously, but the penalty structures differ.

| Offence | UK Maximum | Queensland Maximum |

|---|---|---|

| Rape | Life imprisonment | Life imprisonment |

| Sexual assault | 10 years (Section 3) | 10 years (14 years if aggravated) |

| Assault by penetration | Life imprisonment | Covered under rape/sexual assault |

| Sexual assault on child under 13 | 14 years | Various provisions, typically 14+ years |

Changes to UK’s policies mean rapists and those convicted of the most serious sexual offences will serve whole sentences without automatic release for early parole. In Queensland, the same applies for rape and there are no exceptions.

Court System

UK: Sexual offences are usually dealt with in the Crown Court with a judge and jury. Some lesser offences can be dealt with in the Magistrates’ Courts.

Queensland: In Queensland, serious sexual offences are rape and aggravated sexual assault are considered to be indictable offences. These are usually heard in the District Court or Supreme Court. In addition, some lesser sexual offences can be dealt with summarily in the Magistrates Court, if the defendant chooses that.

Sex Offender Registration

Both the UK and Queensland operate sexual offender registries, and although they are different, they are both valid.

UK (Part 2, Sexual Offences Act 2003): offenders on the sex offenders register (called the notification requirements) must notify police of their personal information including their name, address, date of birth, national insurnace number, details of their passport, their bank account, and information about any house where children live.

To look at how registration notification periods work, an offender with an Indefinite sentence notification is imprisoned for life, while a sentence of over 30 months leads to an Indefinite notification, 30 – 6 months leads to a 10-year notification, and anything less than that or a caution triggers a 2-7 year notification. After a minimum of 15 years for Indefinite, an offender can apply for review. Queensland, under the Child Protection ( Offender Reporting and Offender Prohibition Order) Act 2004, Child Protection Registries are for offenders of crimes against children. Reportable offenders are required to report to the police their name, their address, where they work, their car, their internet service provider, their email, their chat usernames, and their passport. Depending on the offence and how many times the offender has re-offended, the reporting periods are 5 years, 10 years, or life. In 2025, “Daniel’s Law” came into effect in Queensland, which added a 3-tiered public register system where the public can see some limited information about certain offenders.

| Registration Element | UK | Queensland |

|---|---|---|

| Primary focus | All sexual offences | Primarily child sex offences |

| Public access | Limited (Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme) | Three-tier system under Daniel’s Law (2025) |

| Bank details required | Yes | No |

| Internet identities required | Yes | Yes |

| Review possible | After 15 years (indefinite) | After 15 years (life-long) |

Bail Considerations

Both jurisdictions impose strict conditions on bail for sexual offence charges.

UK: Bail is governed by the Bail Act 1976. Sexual offences typically involve conditions such as residence requirements, non-contact with complainant, surrender of passport, and reporting to police. There’s a presumption against bail in certain serious cases.

Queensland: Bail is governed by the Bail Act 1980. Courts consider whether there’s an unacceptable risk of failing to appear, committing further offences while on bail, or interfering with witnesses. Sexual offence charges commonly result in conditions restricting contact with complainants and children.